Don't. That's right. Don't try to build without an architect. It is best to team with your architect through the entire design, permitting, and construction process. It is most efficient to simply trust the architect to do what is best, and ask how you can help make the process more streamlined. Easy to say because I'm an architect, right? The fact is, how could you successfully manage an architect's work unless you have experience doing architecture? Otherwise, you are trying to manage something you know absolutely nothing about (although you may assume you know something about it), and you would be attempting to simplify a very complex profession. There's a reason why architects are required to earn a specific professional accredited architecture degree (or more than one degree), document and complete several years apprenticing under national architectural registration board requirements, pass all the state board exams, maintain continuing education credits, and carry $1 million or more in liability insurance. Close to 75% of my class did not graduate from my architecture program, and most of the ones who did graduate are still not licensed architects. To state it simply, the profession is very complicated and requires a high degree of specialized knowledge, creative insight, technical experience, and ability to synthesize and apply legal aspects of building code and business issues. Anyone who thinks an architect just draws a floor plan to get a permit is very short-sighted. Most people don't actually know or understand what architects do. Same for someone who actually thinks they sketch their own ideas on graph paper and hand it to an architect to get it permitted and built without making any changes to it. The people who try to take on the architect's work on their own are always the ones who don't really understand what architects do and believe they could manage this unknown work. If you consider the people who do tons of construction projects, they always hire an architect and understand the benefits. They also understand what architects do and have the better judgement to know they should not take on this work on their own. Did you know federal laws limit the use of the term, "professional," to the professions of doctor, lawyer, engineer, CPA and architect due to the high degree of required training and specialized discretion involved with performing the work?

Managing the work of the architect on your own puts all of these ideas into question, and it's not prudent for anyone to question their architect without first understanding the entire background behind the situation. This would require the architect to explain the ramifications of land use code, building code, construction methods and materials, schedules, budgets, experience on previous projects, etc. This is why people hire an architect: because they don't know how to do these things (successfully). An architect is capable of explaining all these things to help the client make informed decisions, but why should he/she? The architect is already legally required to follow all these rules to ensure the building is safe and functions properly, and furthermore, the architect truly wants the building to be the best it can be under the parameters that govern it. Questioning your architect leads to a lot of time spent explaining why something must be designed a certain way which leads to less time spent completing the project, more time spent on professional fees, and eventually frustration from the architect.

A client does have the right to question the architect, but they should focus on setting goals and expectations instead of aiming to change the way the work gets done. It is the job of the architect to understand the goals and ensure they are achieved. Questioning the architect's methods just inhibits this. I do encourage collaborative feedback, however. The distinction between the two is really a matter of respect and trust that the architect is being prudent to get the project completed in the best way possible. I believe architects receive more scrutiny than other professionals because there is also a layer of creativity and aesthetics tied to the design decisions. I always try not to consider aesthetics when solving any design problem, so the solution will be as pure as possible. The aesthetics are a latent effect of the function.

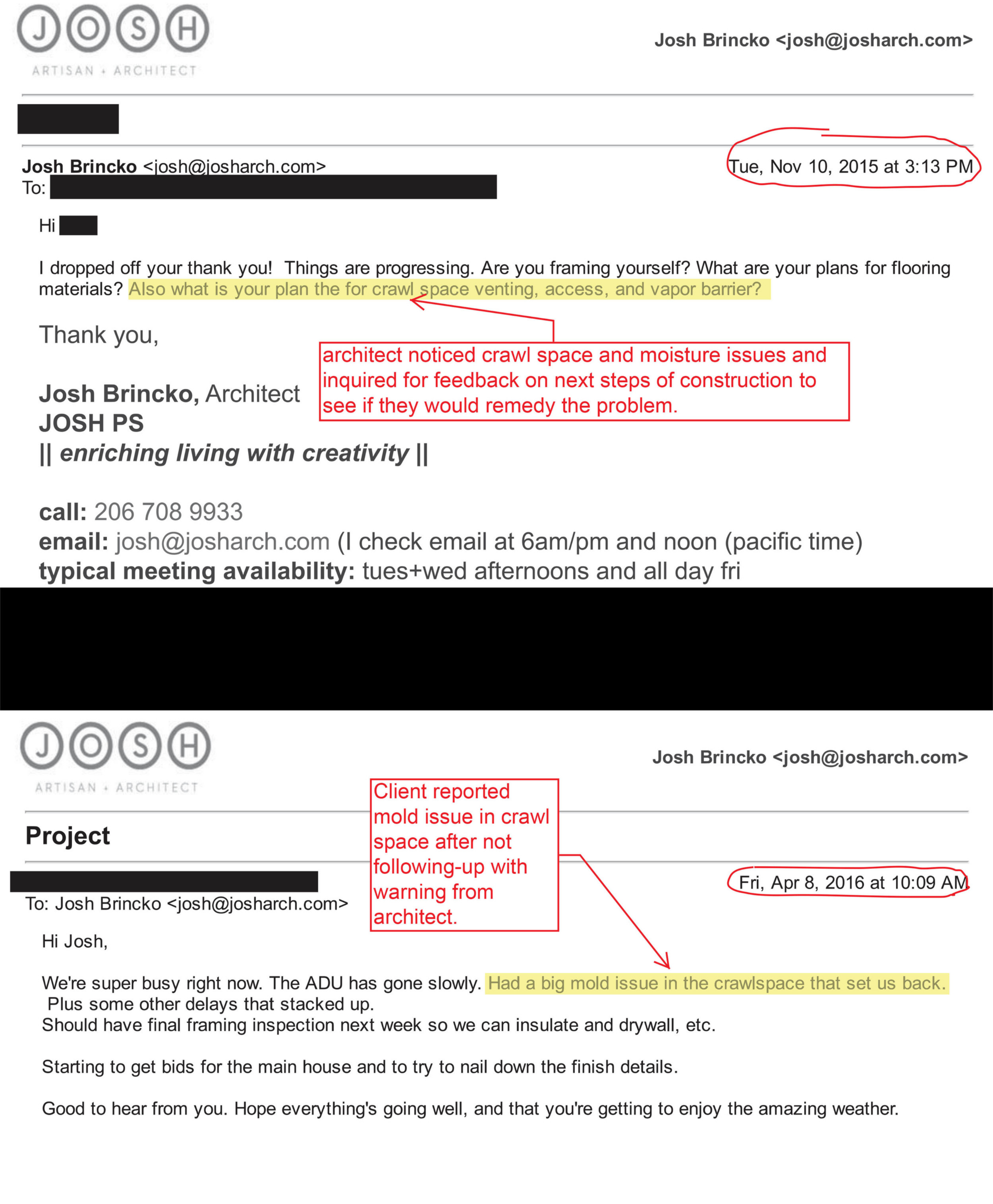

A builder I used to work with was a prime example of an uniformed party that would repeatedly attempt to manage the architect, and he would normally do it in an effort to try to skirt the rules. This is why I don't work with that builder anymore. At the end of a project, he would leave the client exhausted which reflected poorly on me. He is actually capable of building a good product, but the process of getting there always caused the client unnecessary stress, drama, errors, and consequently time and money. He would commonly start building the projects without consulting with the architect, and he would reference permit drawings for information as he built. Permit drawings only include some very limited information on a checklist provided by the building department, but they include none of the specifications, instructions, or dimensions necessary to actually build the project. The building department does not need or want this level of detail (such as finish materials, waterproofing details, anything related to aesthetics, etc). So it is simply not possible to build the client's vision from permit drawings. More detailed construction drawings which contain all the specifics are required. (See my earlier post on construction drawings vs permit drawings.) So this particular builder thought he could earn more money by convincing the client to spend more money on construction by "kicking out" the architect once he had the permit. He actually told me this. So the builder was essentially trying to build without drawings which is like trying to cook a recipe by only looking at the picture in the cookbook and not reading the instructions or ingredients. Good luck. This inevitably caused the builder to hit road blocks, blame it on the architect, and tell the client he needed the architect to "fix" the drawings. In reality, the architect really needs to finish the design process which then becomes more difficult if there are construction deficiencies to work around which the client did not want to spend time or money to unbuild and rebuild. As a result of this builder's approach, he would commonly not read the drawings and install the wrong materials. On one project, he put the wrong siding on an entire wall, put the wrong light fixtures in all rooms, nearly neglected to maintain the required fireproofing between tenant spaces, improperly built waterproofing details, neglected to properly sequence venting details, simply forgot to put siding on certain areas, and authorized the order of windows that did not comply with the energy code - all while understaffing the project which caused the build to take 2 to 3 times longer than it should have (which cost the client months of unearned rent from future tenants). There was literally a similar, but larger project being built across the street that started months later but finished months earlier. This all happened because he questioned the role of the architect and was in the habit of not reading the drawings.

This builder would also question things he knew nothing about such as land use code issues. For a simple project he assumed no new parking spaces would be needed since other nearby projects didn't need additional parking. He was right, but he failed to understand the process of getting that approved. I told him I would have to spend time calculating the number of parking spaces needed based on the current code for his situation, then I could determine and subtract the exceptions and exemptions from the parking rules applicable to his scenario which could equate to no additional parking necessary, so his project could get approved. Instead of hiring me to do this, he chose to hire another designer who agreed not to check the codes but to simply submit basic plans without that information pursuant to his request. Public records indicate this did, in fact, result in revisions mandated from the building department, which costs additional time and permit fees. (At the time of this post, nearly a year has gone by, and that builder is still without his permit for a very simple project). This could also end up with extra requirements for additional parking spaces, fire sprinklers, earthquake retrofits and other unnecessary items that an architect can get exempted IF he were to authorize the architect to apply those rules. Instead, he fallaciously decided to manage his architect and now has larger, more expensive (project stopping) planning issues to resolve, and he will have more design fees to pay. Architects have the ability of saving clients and builders time and money, but only if they can do their jobs. Managing the involvement of the professional really inhibits the success of a project and typically makes the construction cost more money due to the chaos and added permitting consequences.

It is not uncommon for a builder to try and circumvent the architect, but this is mainly because they are inexperienced in the work they do and don't understand the role and benefit of the architect in the process. These are not good builders to work with, and they don't even realize that fact about themselves. Think about it: in the role of an architect, I have the opportunity of working on many similar projects at the same time, so I can make direct comparisons on how one builder conducts business over another builder. Each builder works in a vacuum and therefor has little reference for how their workflows compare to one another. I am in an ideal position to monitor the success of many different builders, and it is clear to see that the most successful builders carefully rely on the advice of their architect. It is a major red flag when the builder tries to eliminate the architect and take on that role themselves. Caution. Builders know that architects can hold them accountable for their work, so beware of a builder who says the project is straightforward and they don't need an architect. Don't fall into that trap.

Former clients really learn to trust the judgement of their architect by the time a project is over, and they begin to understand what an architect really does and how the process works. (See my previous post called In Architect We Trust). Clients often learn the hard way about keeping their architect intimately involved, and they frequently tell me, "I wish we would have listened to you when you suggested ....."

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help