Who is Callie?

If you have worked with Josh, you have worked with Callie. She plays a major role at Josh Architects, and she is a major reason why I, Josh Brincko, am somewhat sane. As a husband, dad, architect, teacher, coach, etc, I juggle a lot of things. As an architect, I have many projects in the works, I am excited about them, and therefor, I am constantly thinking about them. In a sense, my clients "rent my brain" to dedicate it to their project. This pulls my attention in their direction, and Callie plays a major role in keeping focus on all this work.

She has been my coworker for many years, and she has an integral role on all projects. She keeps things organized, moving along swiftly, and most importantly has great problem solving and creative skills. Josh Architects has been successful largely in part by her involvement.

Callie, short for Callahan, came from a small town in Nevada and went to a small high school before moving to Seattle to go to college in a big city. This is where I met Callie. I was her professor in a residential design studio, and she clearly excelled in the course and also worked in the cafe on campus. I don’t remember if her projects were any good, but I clearly remember her positive attitude, cooperative demeanor, quickness to absorb complex information, attention to detail, and her eagerness to learn more. She eventually asked if I had any internships available, and although I did not, I figured I should try to create one, so I would not have to pass up on the opportunity to work with such a promising, talented up-and-coming designer.

At the time, I was working on a three story apartment building, with three different layouts of apartment units although each one was somewhat unique. It was a large project, so I asked her if she could quit her job at the cafe, and join me in a more serious role. It was the perfect project to jump in on since each one had components great for learning such as ADA compliance, durable materials, nicely designed kitchens and bathrooms, window and door trims, and custom designed built-ins. With each apartment unit a little different, it gave her the opportunity to receive thorough direction on one unit and to apply that direction with her own insight on the other units that were a little different. She was able to assimilate the information quickly, implement it efficiently, and be flexible as the design changed (as they repeatedly do on most projects). Also during this time, Callie played such a pivotal role when a burglar stole all our computers from the office. She stepped in, remained unphased, and helped in the process of rebuilding without complaining about redoing work that we had lost. You can read about that more here: http://www.josharch.com/blog/2017/6/17/your-architect-lives-with-great-responsibility

She learned a lot on this project and many others for a couple years working with me before she saw a great opportunity to work with a high-end hospitality firm designing hotel interiors. There she focused on over-the-top design experiences for hotel guests while also learning about a broad spectrum of material specifications. She also realized the working environment she was in was less than ideal, so after a few years of learning what she could in the hospitality space, she decided to take a breather. She slowed down and got a job as a barista where she could focus on herself, actually enjoy the great parts of living in Seattle, and charm her customers with her warm personality.

After a year or so of Callie perfecting the perfect espresso drinks, I randomly happened to be talking with another former staff member who also happened to know Callie although I had not been in contact with her for a few years. I was talking about how my firm was really busy and needed to find someone really talented to come help. This is when I was told that Callie was taking a hiatus from design and working in a coffee shop, and she may be ready to jump back in. After a couple text messages, they setup a meeting with me, and she’s been back with Josh Architects ever since. She has truly honed her skills, continues to step up her game, and is a joy to work with. She remains calm under pressure and remains passionate and engaged with her work.

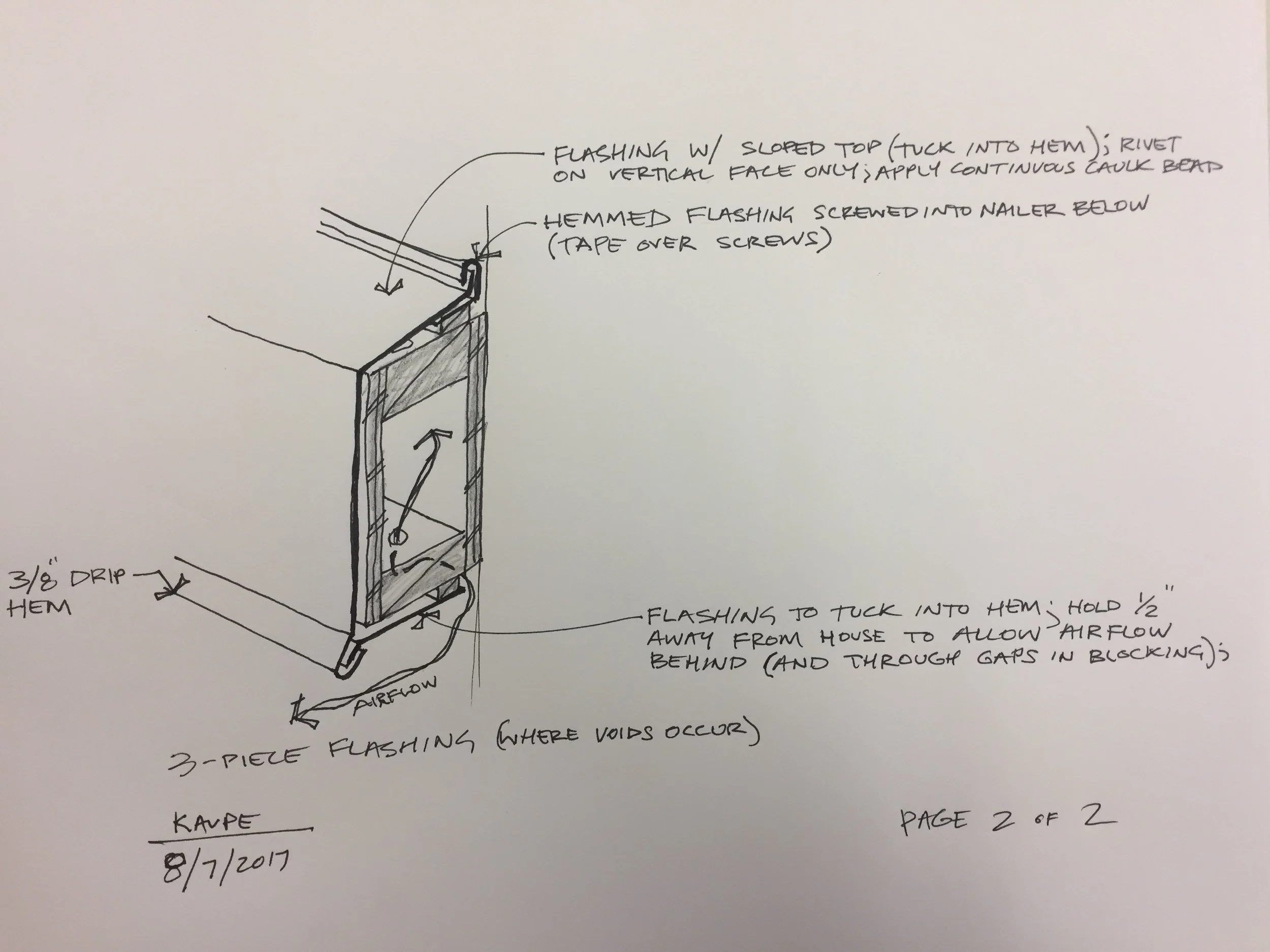

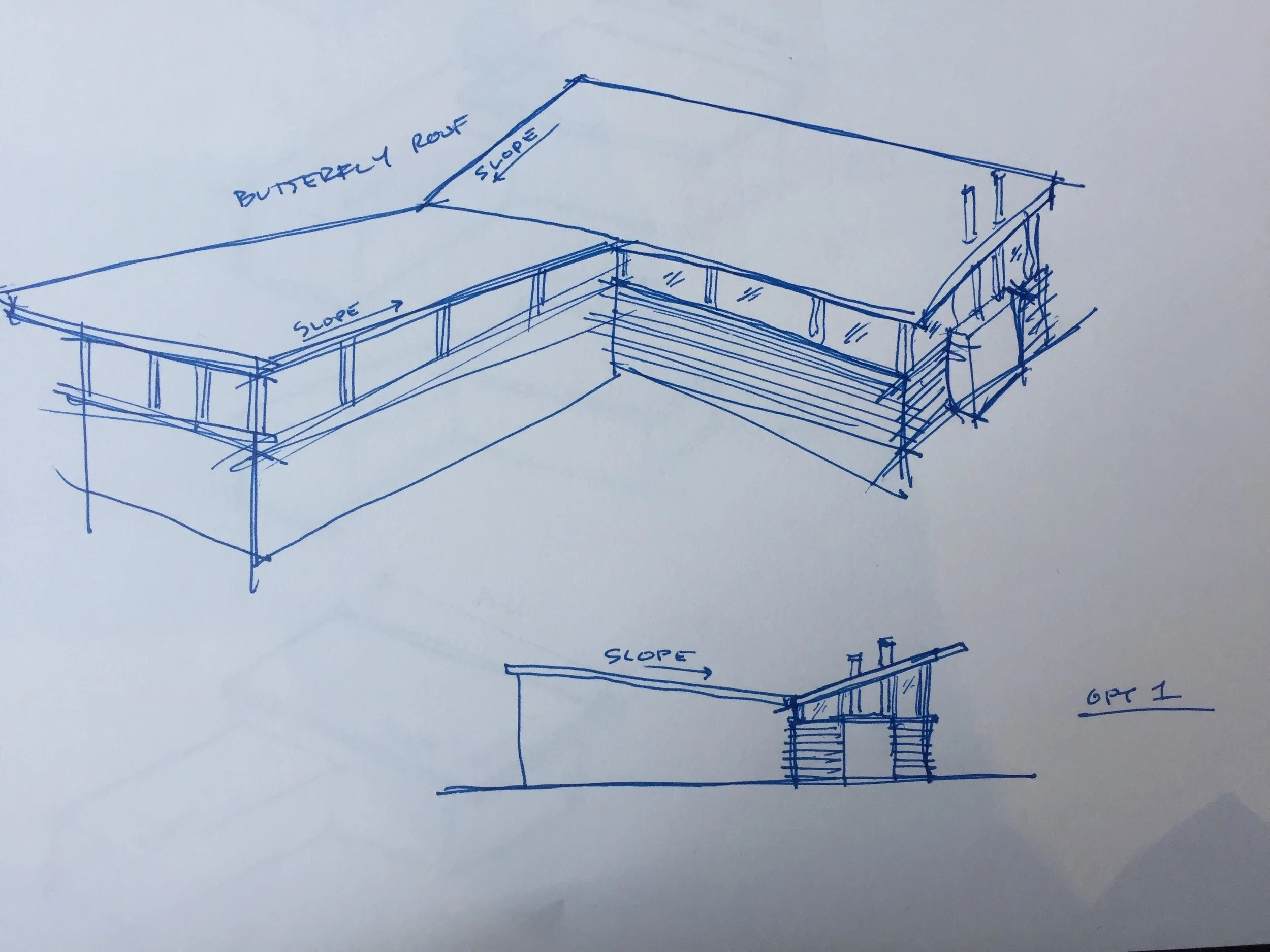

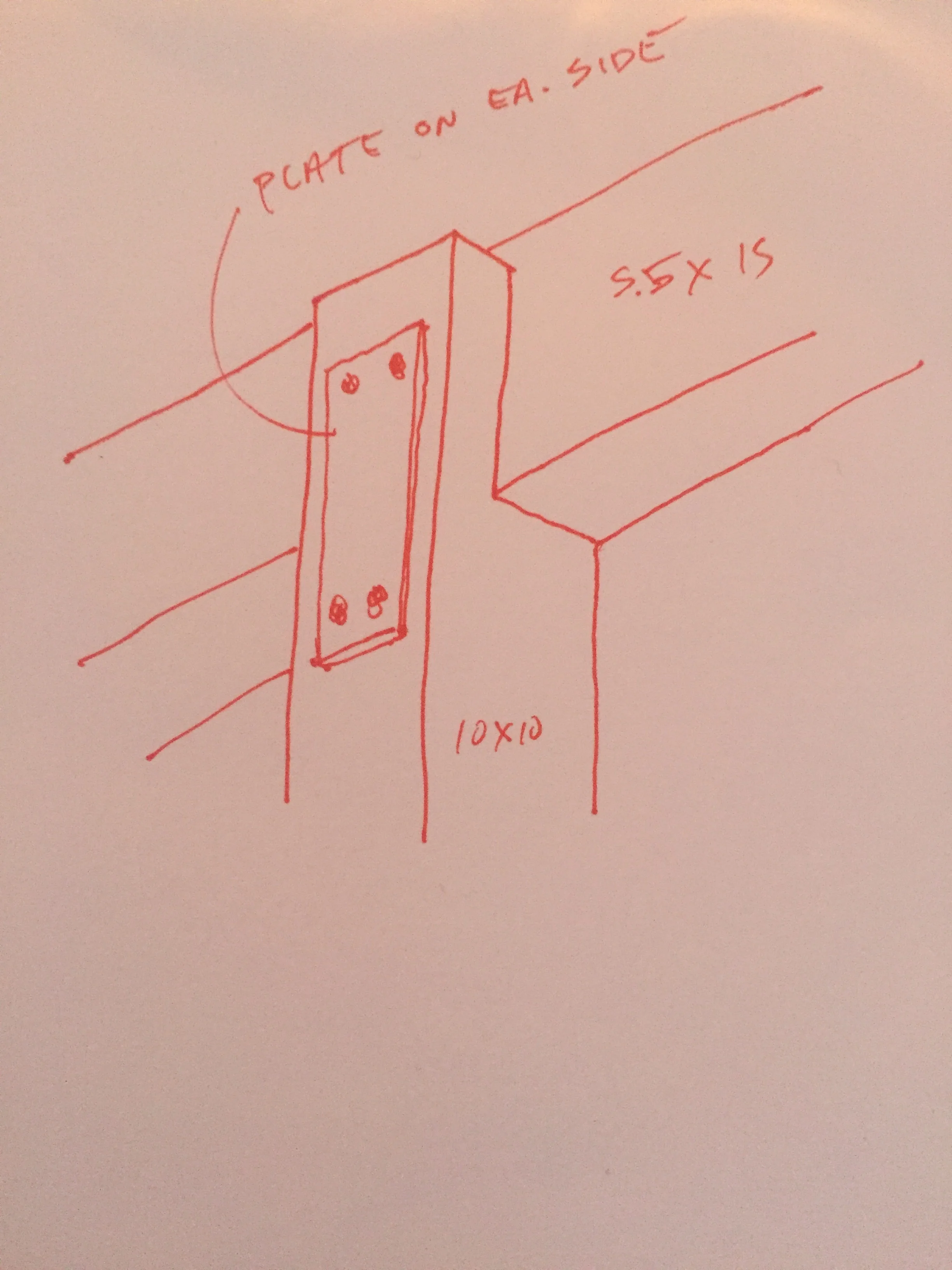

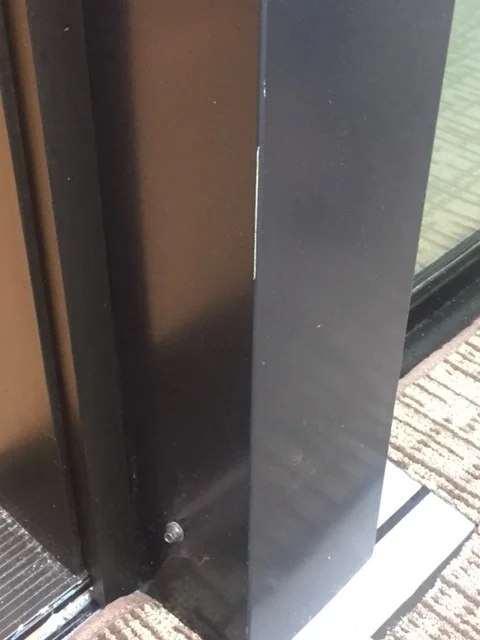

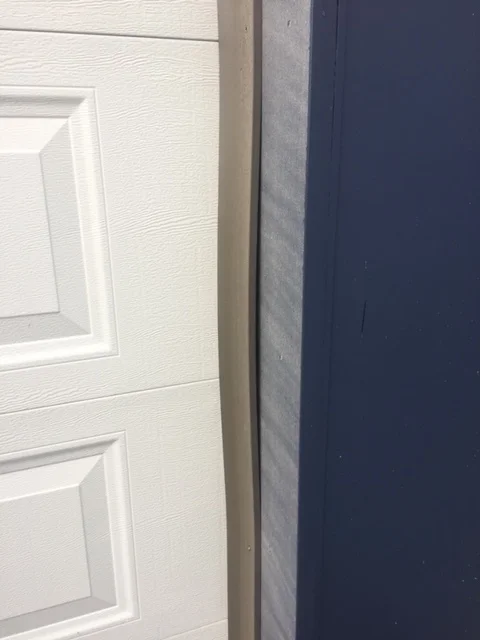

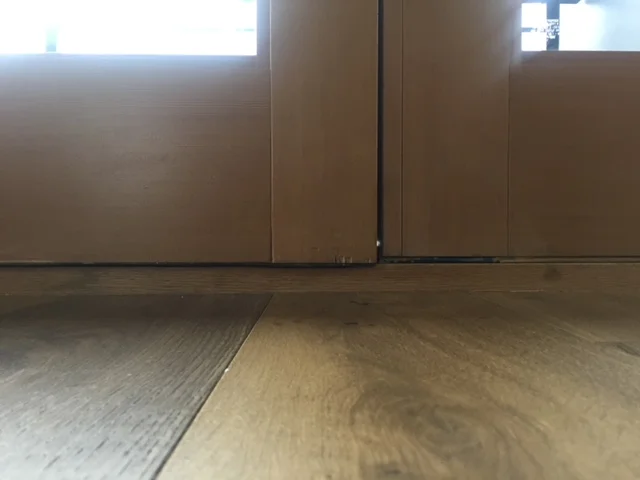

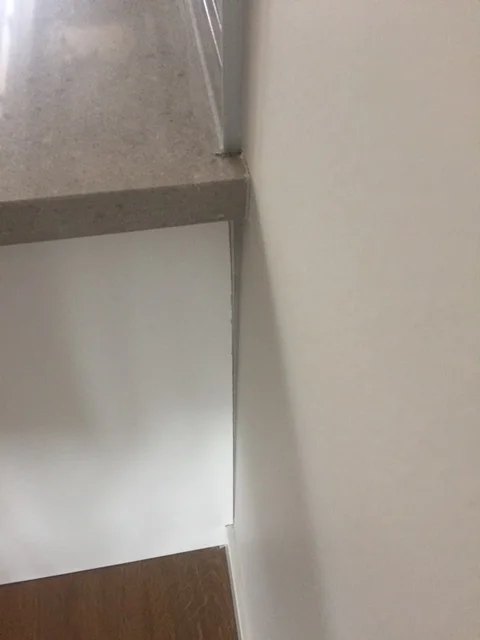

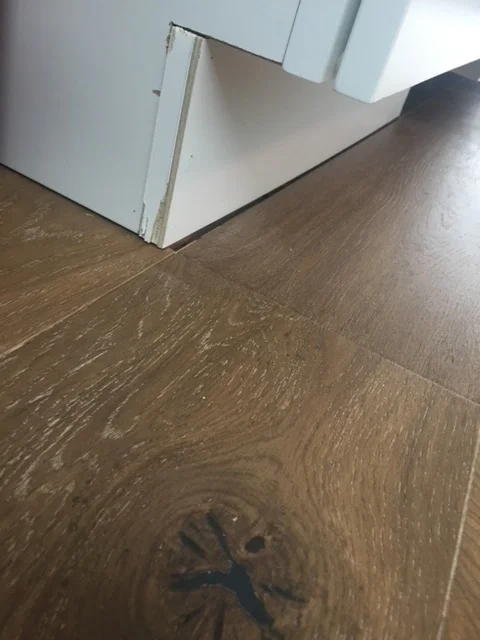

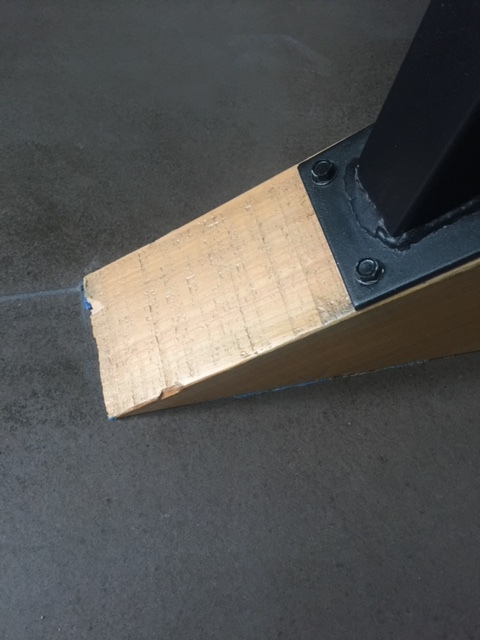

One of the coolest parts about Callie is she doesn’t mind getting her hands dirty. On a few occasions, she has stepped in and helped to do construction labor on a few of our projects. She understands that doing construction is one of the best ways to learn to properly design and draw things. She has done some light framing, decking, window install, weatherproofing, etc.

She is also very good about focusing on her well-being. She regularly does exercise, yoga, eats healthy, goes rock climbing, and enjoys time with friends. She’s very active and also very creative. She has been doing artwork regularly and experiments with different mediums. Woodburning is one of the processes she has recently taken a liking to, and she is very talented (and patient) at it. The wood scraps from our clients’ homes are finding a new life in Callie’s artwork. She has even been commissioned to create pieces for people.

You are in very good hands when you work with Callie, and it’s truly fortunate that she is part of our family. Feel free to reach out to her to say hi (callie@josharch.com) or to ask about commissioning her to do an art piece for yourself or as a gift. She began drawing class at age 3 when her mom noticed her special talent. Over the years, she has realized that art, to her, is less about a set style or topic and more about texture, color, and exploration and finding tension through the combination of unexpected items. She particularly enjoys working with recycled or found objects since she finds beauty in working around their imperfections (angled cuts, awkward sizes, knots, drilled holes, etc). She has collected scrap lumber from our jobsites to reclaim for art pieces as you can see in many of the wood burning below. To Callie, her art is sometimes just about making a piece that will make someone smile. She really enjoys working on commissions for people to create something unique and meaningful to them. It really pushes her out of her comfort zone and challenges her to work in scales, style and subjects which are new to her.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help

Here are some examples of her work: