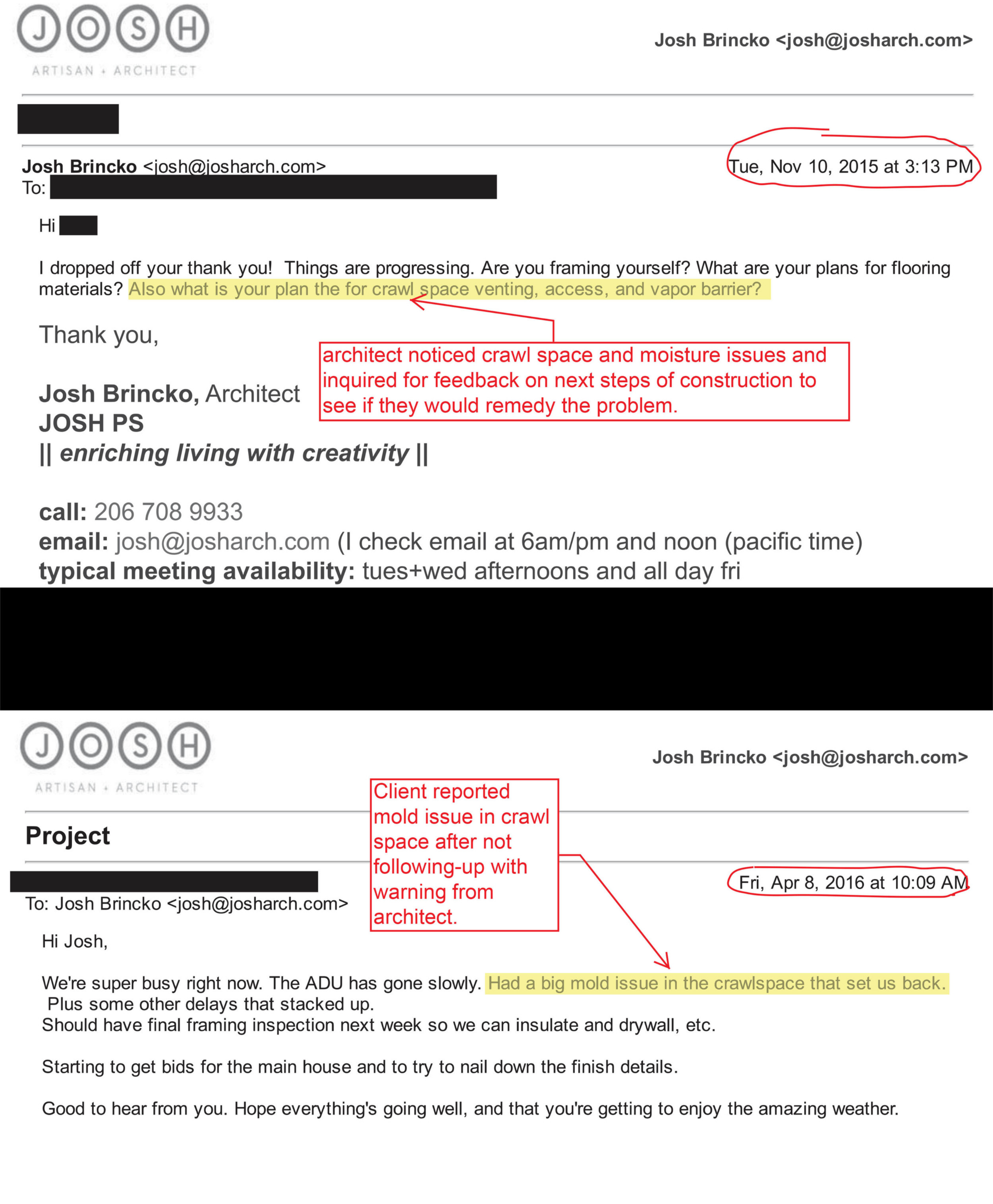

Here's an example email string between the architect and the client. The architect was inquiring about the construction progress after not hearing from the client for several months.

The emails above are just one of so many examples where an architect's involvement throughout the entire construction process is valuable in preventing costly errors. After happening to drive by a client's project under construction, (in a matter of seconds) the architect noticed inadequate crawl space ventilation and wet construction materials which is a perfect recipe for mold. The architect promptly asked the client what their plans were for addressing this issue since the architect had not been consulted by the client after the permit was approved. The client never responded until months later when mold had developed in the crawl space and cost thousands in remediation fees. A few minutes of consultation on phone, email, or on-site meetings easily prevents these issues. The permitted drawings are only detailed enough to state that a crawlspace must be ventilated to satisfy code requirements, but those basic drawings do not actually describe how to build the vents. Although the hourly rate of an architect may seem like an unnecessary expense to a first-timer, it is a wise investment to protect one of the largest investments a client will ever make. Architects design dozens of buildings every year and have inevitably experienced a myriad of issues and have the experience to easily resolve them. Would you give yourself anesthesia to save money before a surgery? Would you represent yourself in court to save money on a lawsuit? Would you refinance your home without consulting with a loan officer? Your home is your biggest investment. It makes a lot of sense to include an architect on your team throughout the entire construction process to protect that investment.

Most people have never built a house or worked with an architect. It is understandable that most people do not know what an architect actually does. Many people have an assumption that an architect draws the plans to help get a building permit - and that's the end of it. Although this is the minimum amount of professional service required by law in some instances, most of the value of working with an architect comes during the construction process. The permit drawings do not actually explain how to build a building. These drawings only prove to a building department that the building will meet the minimum required standards of safety, ventilation, and insulation. A city inspector shows up periodically during construction to confirm these things have been met, barely.

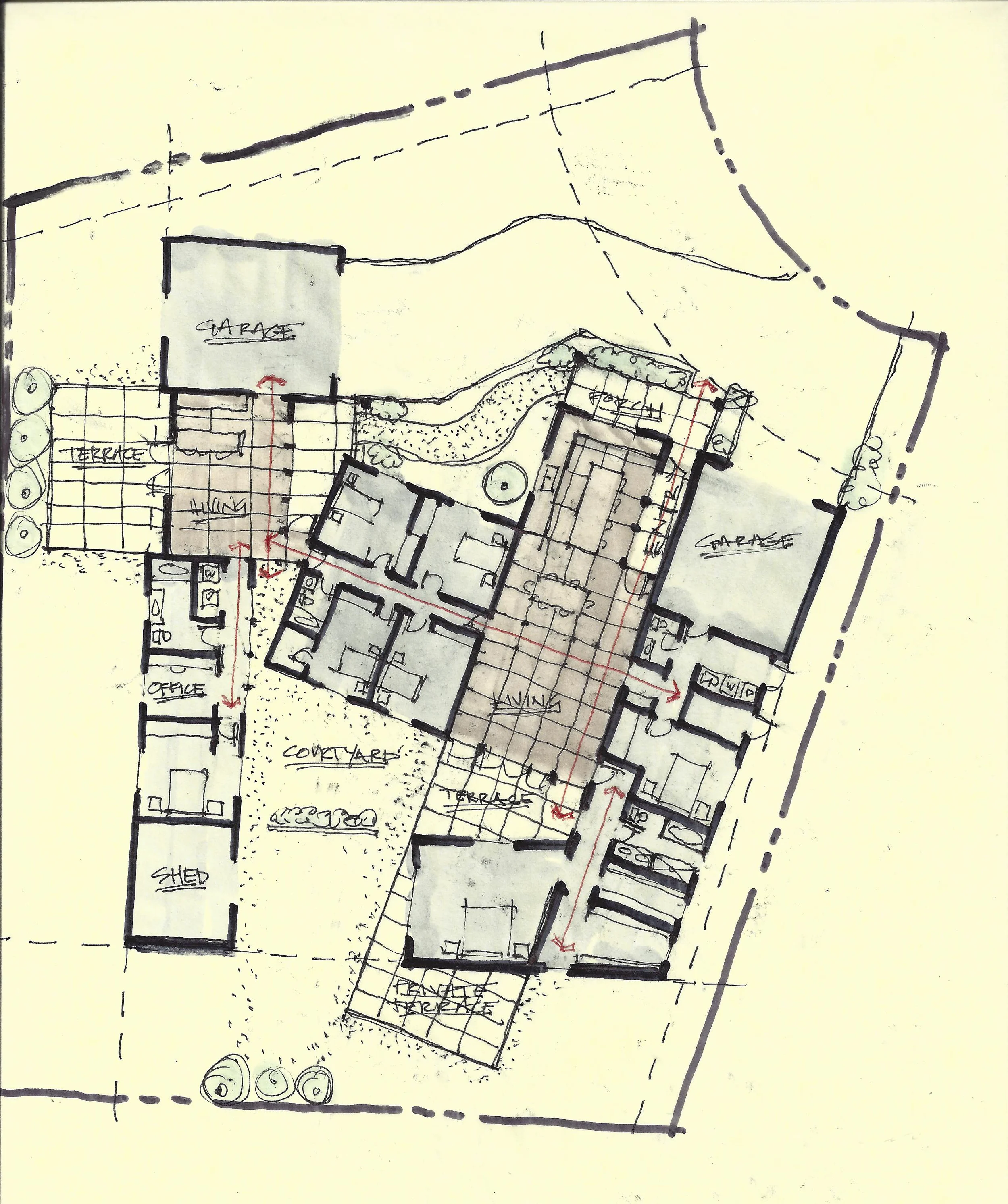

After the building permit has been approved, the architect adds more detail to the drawings to explain specific products and materials and how they will be integrated. This is effectively an instruction manual for the builder that explains how to build the building. This is also a written contract between the builder and the client that explains the level of quality and specific expectations for what is contractually obligated to be built. A higher level of detail on the drawings provides a more clear contract for the contractor to follow, and this helps to ensure the building is built according to the client's wishes. For example, a wall on a set of permit drawings is just two lines that represent the structure and some other materials that the building department is not concerned about. Building from these permit drawings allows builders to build whatever they want since nothing specific is required to be specified on permit drawings. This prevents builders from knowing precisely what to build, prevents them from knowing how much it may cost to build, and prevents the client from having any control over the outcome of the project. Not involving the architect after the permit is approved inevitably causes lower project quality and creates a likelihood for costly errors.

The architect's main value is in designing the details after the permit process to create very specific construction drawings and to regularly advise the client and builder during the construction process to ensure the built conditions will perform properly. This saves you time. This saves you money. This gives you sanity. And this ensures your project will turn out well.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help