The most valuable work I do for my projects is on a jobsite with a pencil. There’s a lot of work that happens before construction begins, but the jobsite is where the most important work for the architect happens. As the builder interprets the original drawings, my guidance on site keeps the construction according to plan. Without my guidance, construction deviates from the plan 100% of the time. Since there’s an inherent disconnect between a drawing and the choreography of what a builder is supposed to build, the drawings could never be fully articulated to the builder. It requires careful, methodical explanation every step of the way to ensure the build matches the plan. Some call it “hand-holding,” but I call it “collaboration.” I give the builder more credit than most since I understand the plans are just a starting point that require practical explanation during construction. This service is called construction administration (CA) which is defined really well in the American Institute of Architects contract B201 section 2.6 http://aiad8.prod.acquia-sites.com/sites/default/files/2017-10/B201_2017.sample.pdf. Some “CA” results in revised CAD drawings, and some results in sketches on plywood on the jobsite.

Does anyone think an actor reads a script for the first time when they perform? No! The actor studies it relentlessly and asks questions. The script is a very loose narrative that gets explained to the actor by the writer over coffee, it gets practiced and modified over rehearsals, and it gets fine-tuned once everyone understands the performer’s talents, nuances, and shortcomings. It is simply not possible to write the script to include all this interpretation on the first draft. It must be performed and modified.

This is exactly what happens during construction. The builder reads the “script” and starts building. As the different trades begin to integrate their scopes of work, it is absolutely essential that the architect is available to interject with guidance on how to interpret the original drawings to make best use of the resources and talents of the builders as the building begins to take shape (and before it takes the wrong shape). This is analogous to a director during a rehearsal telling the actor to say the words from the script louder, with more emphasis, while stomping a foot on the floor - all while the technicians setup the lighting and microphones to adapt the best way of recording these actions.

Please understand this: THERE IS A LOT OF EXPLAINING THAT MUST HAPPEN DURING CONSTRUCTION.

I’ll be frank here. It pisses me of when builders or clients believe they should be able to just use the drawings (produced for the sole intent of getting a permit) to actually build a building without the architect’s involvement. This is completely absurd. It pisses me off because I’m witnessing a client wasting every dollar they have paid me, and I have wasted every minute of my time in working on a client’s behalf. Without the architect’s frequent oversight during construction, the project suffers at the expense of the client 100% of the time. Every single thing that gets built without architect oversight, gets built wrong. This is a heavy statement, but it is true. It is a fact from 18 years of experience. If it’s not 100% correct, it’s wrong. And a simple interjection on-site from an architect like “that plywood needs to overlap this part because...” quite easily fixes everything, and it can become 100% correct. Or a builder may consider it "right" because that's the way he or she wanted to build it, BUT that may not have been the way it was planned, drawn, and approved.

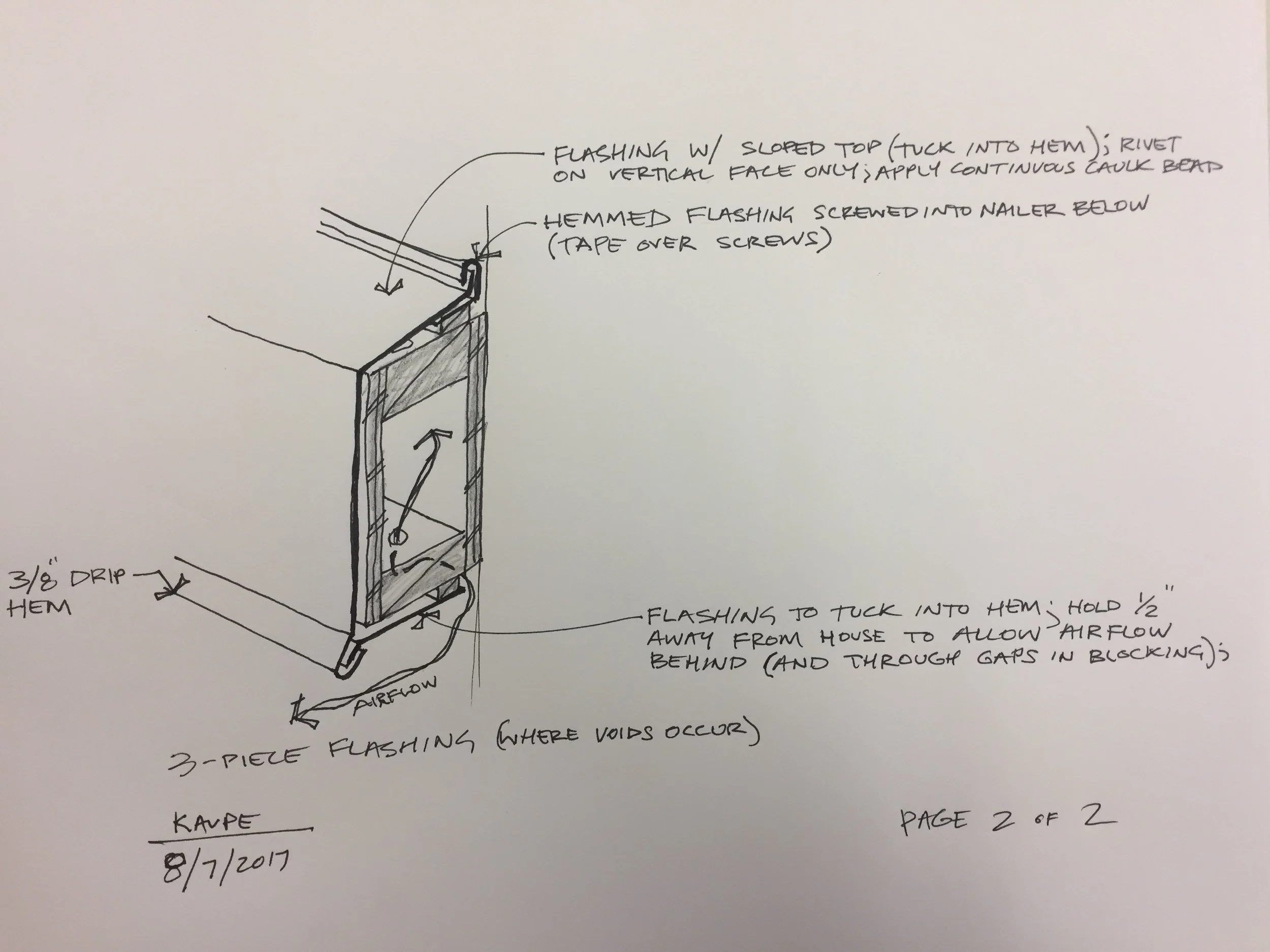

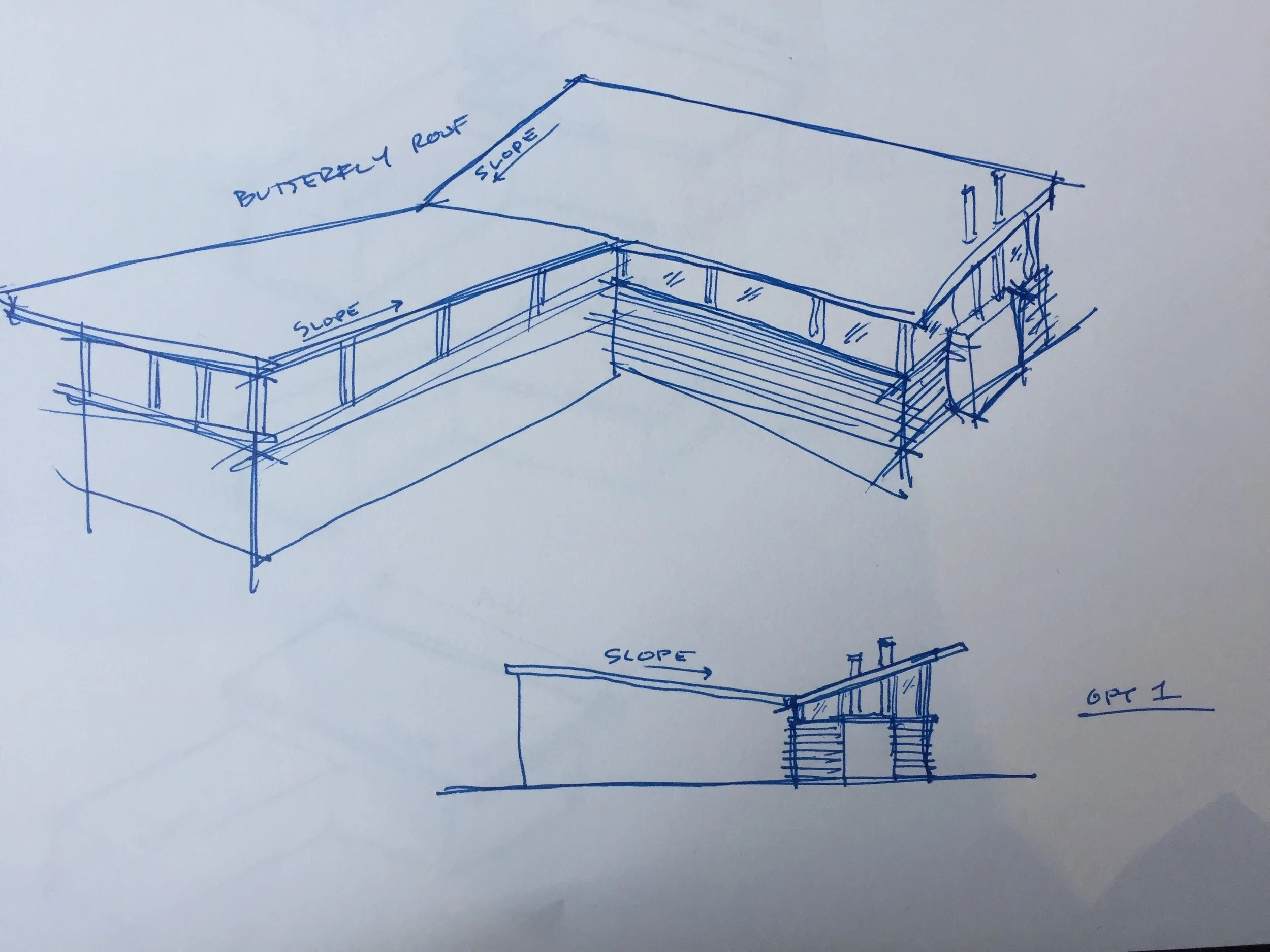

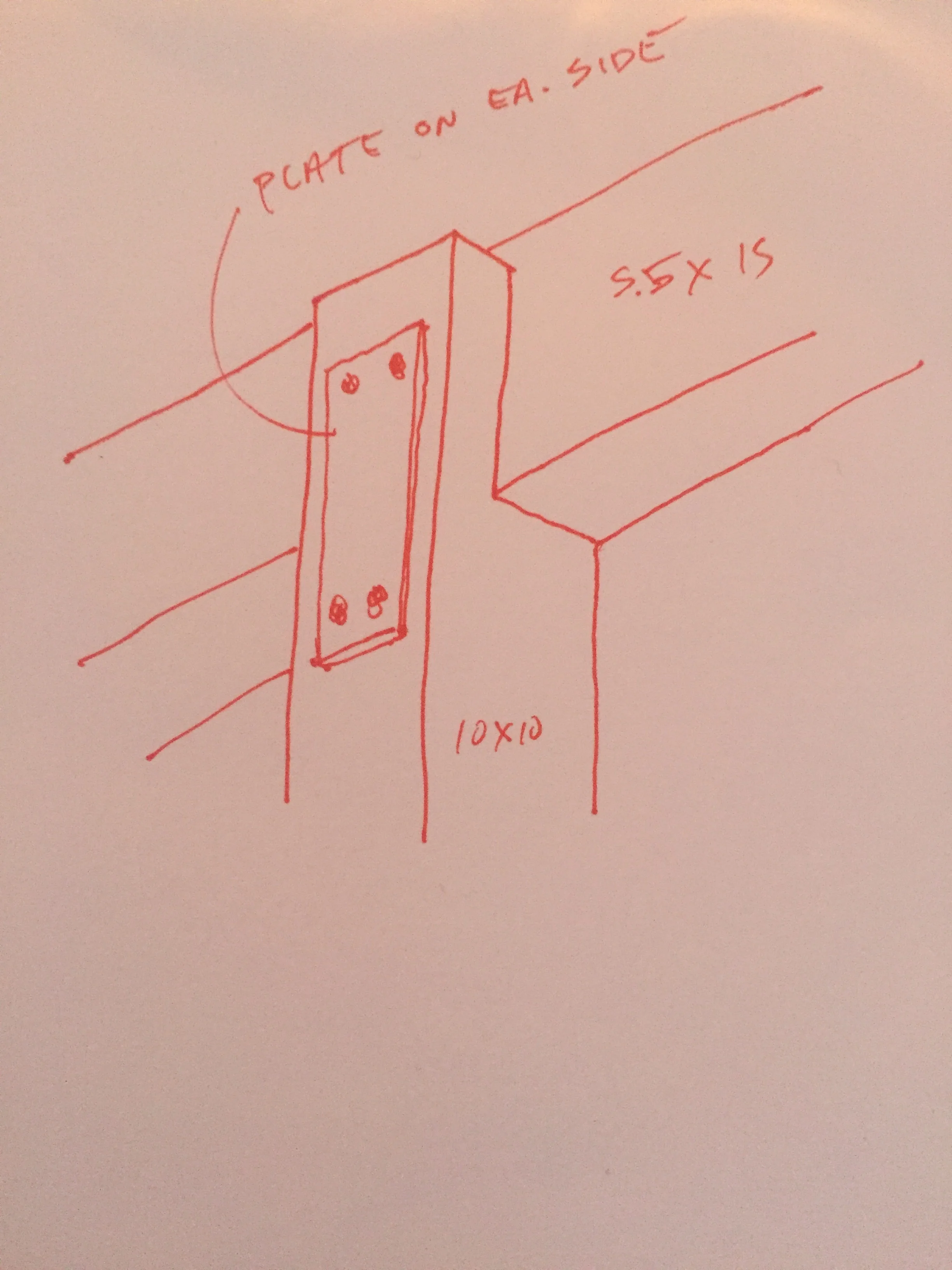

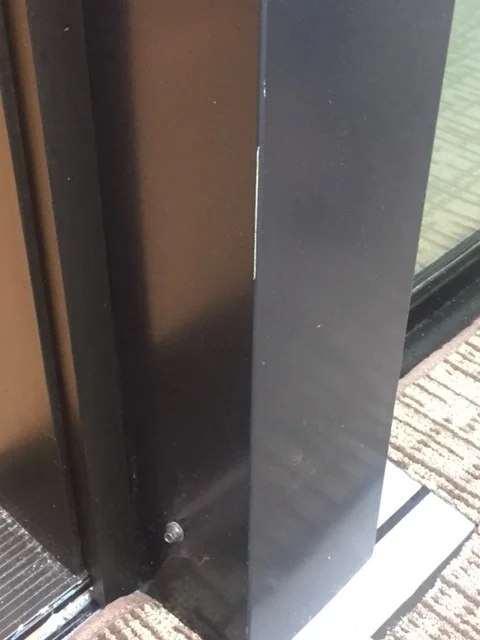

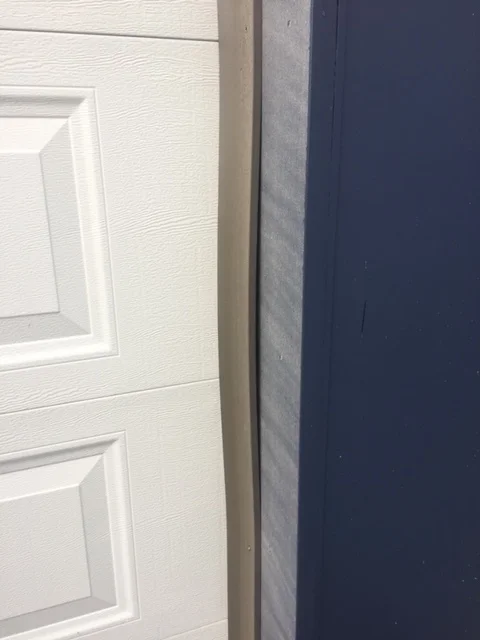

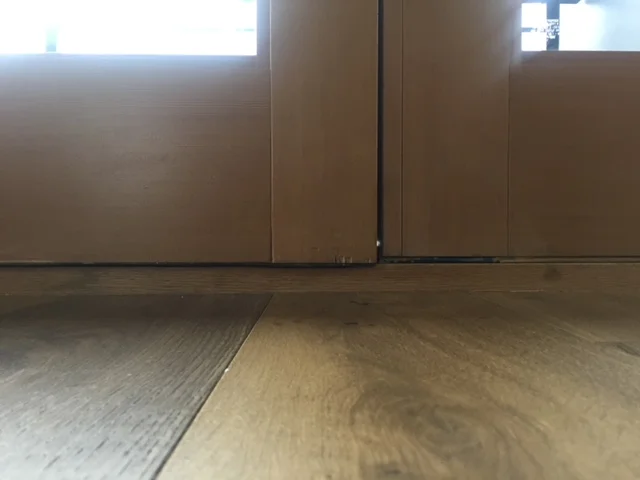

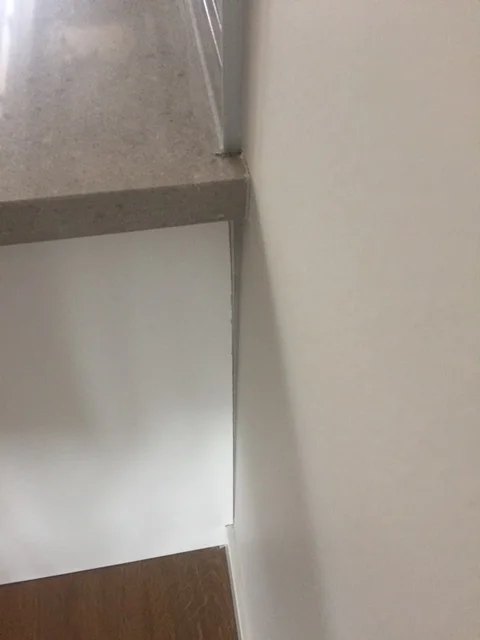

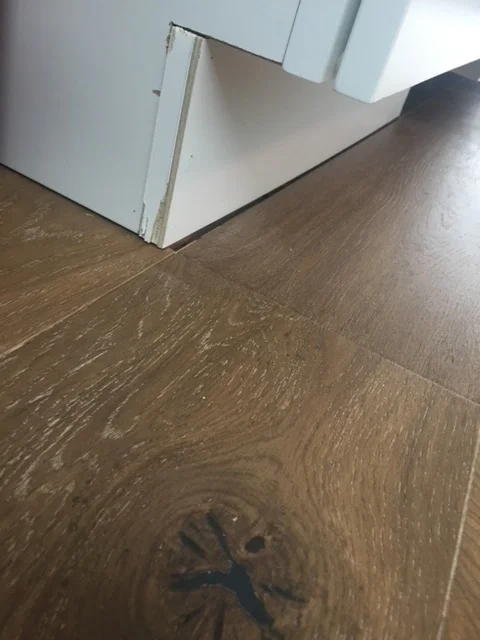

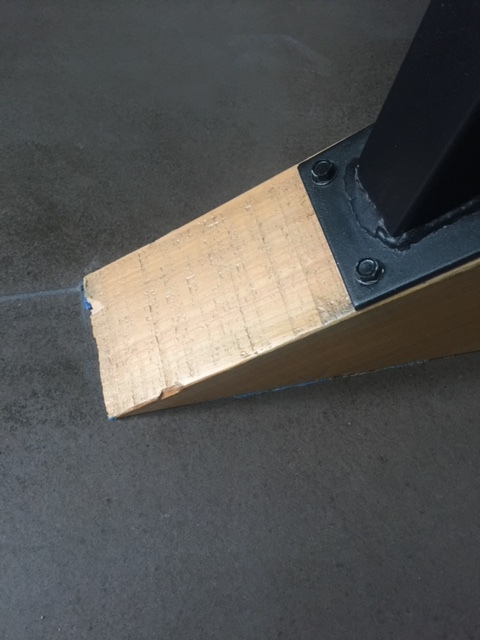

Much of this explaining happens on a jobsite while I explain the concept to the builders and sketch the idea on the floor, or the wall, or whatever surface they are trying to build. These sketches bring it all together using language a particular craftsman understands, and builds upon his or her particular talents. These sketches explain how to get out of the current situation and move onto the next one while getting the intended result without spending any more time or money. In fact, these sketches often will save time and money when done at the right time (which proves frequent involvement from the architect is valuable).

Here’s a collection of some of my sketches that are priceless in conveying a concept to a builder. They initiate that “light bulb moment” where the builder finally “gets it,” so they can spend the next 100 hours building something the way it was planned in the drawings - not the way they think it’s supposed to be, or the way they did it last time, or the way that makes them the highest profit.

If you’d like to learn more about our design process, visit www.josharch.com/process, and if you’d like to get us started on your project with a feasibility report, please visit www.josharch.com/help